“Marketing can be complex, but it doesn’t need to be complicated.”

Wise words from Marc Pritchard, chief brand officer of Procter & Gamble, at this year’s ANA Masters of Marketing conference. As the hype around AI and algorithmically-driven media escalates, Pritchard attempted to re-center the conversation around the fundamentals of marketing. It’s a message our industry would be smart to follow.

Yesterday I keynoted RMN Ascendant’s first-ever “Brand Day” in New York. My presentation concluded with this following slide—a set of principles that brands should follow to achieve better results with their media spend, many of them violating the current orthodoxy of how brands invest in media.

If the index card seems familiar, that’s because it’s modeled on the personal finance index card created University of Chicago Professor Harold Pollack that went viral and was ultimately published as a book: “The Index Card: Why Personal Finance Doesn’t Have to be Complicated.”

Brands are unfortunately wasting a good portion of their media spend today, largely due to institutional factors. While they almost all have the same goals—achieving fame for their brands that results in incremental sales growth—few are implementing the practices that will achieve those results.

Instead, they’re incentivized to achieve KPIs that are weak proxies for actual performance and which can easily be gamed. Pritchard has espoused the marketer’s principles of maximizing reach, effectiveness, and efficiency with their media spend. The principles are nuanced in their application and execution. While many brands aspire to the same objectives, how they put them into practice often yields sub-optimal results.

I believe that brands can do better, but it will require organizational iconoclasts willing to agitate for change. Here are the principles they should promote.

Advice for Brands

1. Buy “expensive,” well-diversified media that reach real audiences.

It’s counterintuitive for brands where cost-efficiency is religion, but certain media is expensive precisely because it is valuable. That’s always been the case with TV ads, and yet with performance ads brands struggle to stomach higher CPMs and CPCs.

Within the retail media channel, less expensive ad formats (sponsored products) and targeting tactics (branded search) correlate to higher ROAS. Similarly, the reverse is true of more expensive formats (sponsored brands) and targeting tactics (conquesting) That’s why brands so often gravitate to sponsored product branded search – it’s great at meeting ROAS goals.

But brands don’t really want ROAS at the end of the day—they want incremental sales. The good news is that it’s achievable if they’re willing to invest in more expensive ad formats and tactics. Sponsored brand conquesting ads carry the highest CPC, but they also produce the best iROAS. Maybe the price is actually worth it?

2. Never buy using black box algorithms like PMax or Advantage+. The company on the other side of the table knows more than you about this stuff.

Brands shouldn’t stand for the lack of transparency in black box AI optimization tools. There’s no good reason that media companies shouldn’t provide visibility into where these ads run—especially with brand safety at the forefront of brands’ minds. I suspect the lack of transparency from Google and Meta is due to the high volume of impressions they’re pushing to their audience networks—by far their least valuable inventory because it’s ridden with bot traffic.

Why would they push impressions to their audience networks if it’s all bot traffic, you ask? Because that bot traffic is perfectly capable of delivering the KPIs most brands are after—viewable impressions, click-throughs, conversions, and ROAS.

The core properties of Google and Meta are generally clean environments (brand safety notwithstanding) for delivering ad impressions to humans. But when their audience networks are thrown into the mix, suddenly their traffic can be majority bots. Any brand that advertises using these black box AI tools should expect that’s what their impressions are running against.

3. Put 20% into new media channels. That’s where CPM arbitrage exists.

Brands are constantly looking for advertising arbitrage opportunities to maximize returns on undervalued inventory. But once a media platform reaches mass advertiser adoption, these instances of arbitrage are ephemeral. What happened when D2C brands began to flood Facebook and Instagram to acquire new customers? Every D2C began to bid for the same customers, pushing up ad prices to where the arbitrage ceased to exist.

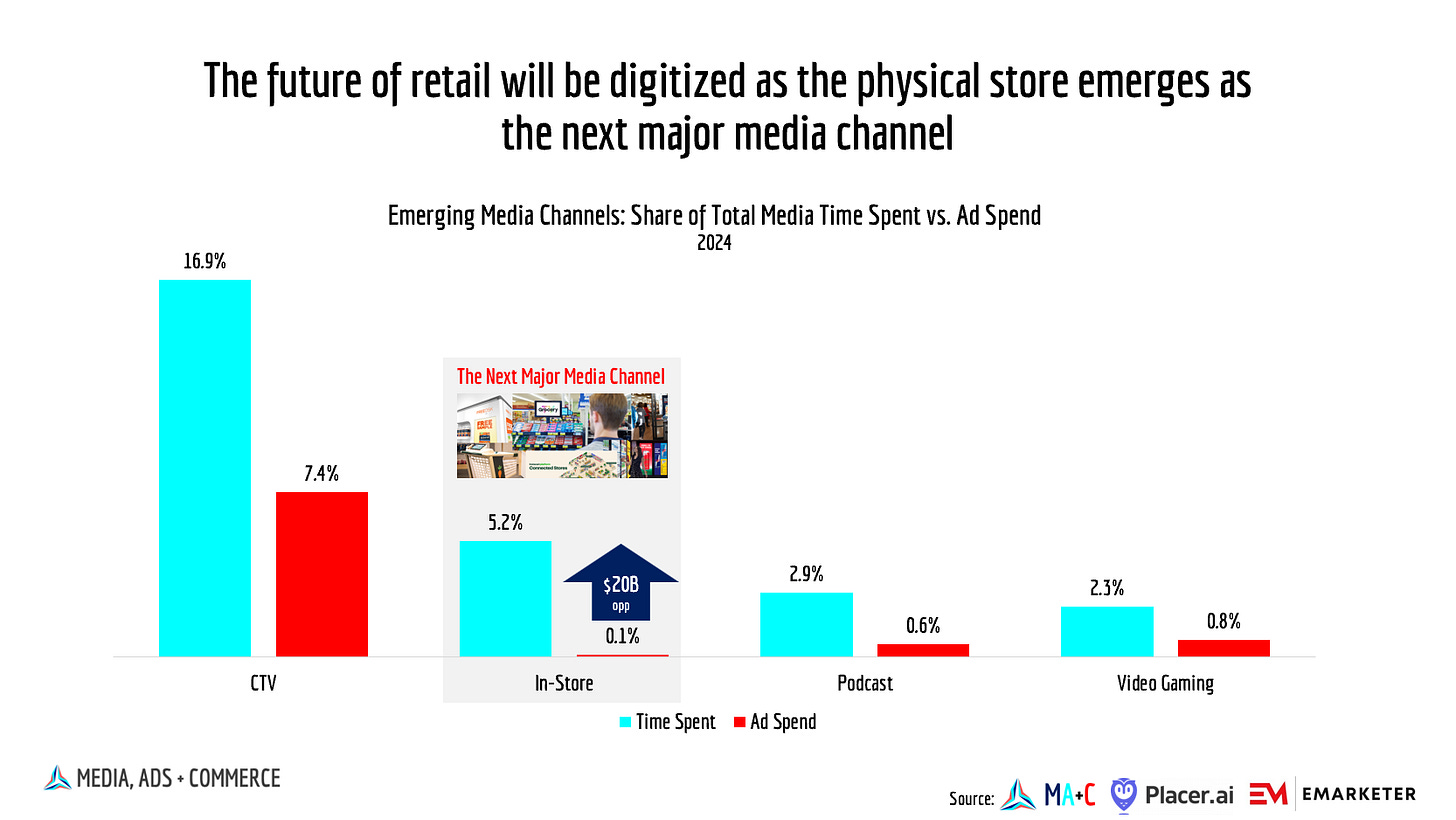

Smart marketers don’t need to rely on performance data to invest in new channels. Instead, they’ll embrace their marketing intuition about which emerging media will work for their brands, and why. Current underinvested opportunities like CTV, podcast advertising, in-game advertising, and in-store retail media all have something important in common: nascent measurement capabilities. That this lack of measurement certainty deters performance advertisers is a feature, not a bug. These are excellent venues for brands to get seen, heard, and noticed, ultimately driving sales performance.

Brands should commit to shifting 5% of their linear TV dollars to in-store advertising by the end of this year. Will it happen? Probably not. But it’s a way for brands to reach key audiences more efficiently and influence purchase.

4. Pay premium CPMs for premium media. Cheap reach is neither cheap, nor reach.

Brands routinely complain about the RMN data premium on top of existing media costs for off-site campaigns. They will tend to opt for “cheap reach” on the open-web to meet cost-efficiency goals. In doing so, they sacrifice media and audience quality to keep their KPIs check while ultimately failing on all objectives simultaneously.

Buying “cheap” means buying open web programmatic inventory, most of which runs on bot traffic that verification firms fail to detect. These impressions deliver only the appearance of reach—not actual reach. And if it’s not actual reach being delivered, then even a lower average CPM doesn’t mean it’s cheap.

That P&G appears to be ramping investment in off-site retail media is a signal to pay attention, and that perhaps the premium CPMs are worth it. P&G wants to achieve 90-100% reach within its core audience segments. Is it possible they see off-site retail media as a means of driving incremental reach among these targets?

5. Maximize investment in contextual media like in-store or category-relevant TV and digital content.

In the rush to buy into the promise of “ad personalization,” brands have begun to ignore a more important variable in campaign success—the context in which the advertising is experienced. Contextual relevance is key for brands establishing the mental availability so critical to influencing brand choice at the shelf.

One of my favorite examples of contextual media are product samples. Consumers get a multi-sensory experience of the product in the environment where it can be purchased. A meta-study of product sampling campaigns show how it can drive trial among new-to-brand consumers, some of whom continue to purchase the brand into the future driving big gains in iROAS over longer attribution periods. These long-term shifts in consumer purchase behavior depend heavily on the value of the context in which the media is delivered.

6. Pay attention to programmatic waste. Avoid advertising on any media you’ve never heard of.

Brands too often fail to look at the detail of their programmatic advertising campaign reports. Many have been lured into a false sense of security with reported IVT levels of 1-2%, making it seem like an issue existing only on the margins. A closer look at these reports would reveal a large percentage of impressions reported as “non-measurable,” often because the verification javascript tags are blocked—by fraudulent websites that don’t want that transparency. Sites identified as MFA are also misunderstood to simply be low-quality clickbait sites, when the reality is many are IVT magnets – auto-generated fake websites designed to maximize campaign KPIs for predominantly bot network traffic.

Brands must re-assert control over these campaigns, and that begins by taking a look at the list of publishers the campaign is running on and visiting the sites. In all likelihood, most of these URLs will be obvious junk content that actual internet users don’t visit. If it’s a website you’ve never heard of, it’s probably not a real website.

7. Make agencies and platforms commit to a fiduciary standard.

Principal-based buying has disrupted the traditional agency model, undermining the trust between brands and agencies by introducing a conflict of interest to agencies’ media recommendations. The lack of transparency erodes trust when the client can no longer be sure the agency will optimize according to the client’s interests rather than their own margins.

Why do brands stand for it? Because the agency’s economies of scale allow it to buy large pools of inventory at reduced rates that can—at least in theory—get passed on to the client. In essence, brands are willing to trade transparency for “cost-savings.” Although in giving up this transparency, brands lose the ability to assess whether it really amounts to cost-savings since they don’t know what they’re giving up in media effectiveness.

Large media platforms are now engaging in the same practice. Notwithstanding Meta’s recent foray into principal-based buying, the black box AI tools that are quickly gaining adoption come with this same conflict of interest. Google Performance Max and Meta Advantage+ pool the platforms’ inventory—inclusive of their off-platform audience networks—and get doled out via AI algorithms. But are they optimizing the advertiser’s performance or their own?

Until brands demand that both agencies and platforms commit to a fiduciary standard, financial interests will remain misaligned. Brands will effectively be competing for the same margin with “agents” who hold an asymmetric information advantage over them.

8. Promote incrementality measurement over ROAS to drive dollars into channels that actually perform.

Digital advertising remains a ROAS-dominated ecosystem, seemingly committed to its original sin of optimizing to the wrong metrics. While the industry lacks consensus over an incrementality measurement standard, brands must push for progress on this front. Otherwise their media allocations will be sub-optimal at best and detrimental at worst.

Brands with the courage to leave ROAS behind and embrace incrementality measurement will achieve better results—not merely driving up their vanity metrics, but actually improving marketing effectiveness and driving up incremental sales.